|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Modern Sculpture page contains 70 images of Neoclassical, Baroque and Modern sculptures taken at

the Getty Center, plus a Houdon from the Huntington Library which was shown in a Houdon Exhibition and

the Tivoli-type bust of Caracalla from the British Museum, shown in comparison with the Cavaceppi bust.

Click an image to open a larger version.

Use your back button to return to this page.

|

|

Getty Museum Index

Getty Paintings

Architecture 1300-1650

1650-1900

Getty Sculptures Index

Ancient Sculpture Getty Decorative Arts Index

Modern Sculpture Furniture

Bronze Sculpture Decorative Art

|

|

Anne de Vermenoux Houdon 1475 LG

(1333 x 2100)

Madame Paul-Louis Girardot de Vermenoux, nee Anne-Germaine Larrivee (1739-1783)

Jean-Antoine Houdon (signed 1777), marble, on loan for exhibition from the Huntington Library.

Carved by the most celebrated portrait sculptor of his time. Houdon depicts Anne-Germaine Larrivee

in an unguarded moment, turned to her right with an affectionate smile on her lips. She wears a delicate

lace-trimmed garment and a cloak which wraps both her body and the pedestal on which the bust stands.

This exquisite sculpture was carved by Houdon from a single massive block of fine-grained white marble.

Shrouded in mystery since its first appearance in the Salon de Paris in 1777, this sculpture had been confused with a Houdon portrait of Baroness de la Houze by the time it was bought by Henry Huntington in 1927, and it was displayed under that name until 2003, when the sculpture was loaned to the Getty Museum for an exhibition of Jean-Antoine Houdon’s work. It was identified by Anne Poulet, who was the curator for the Houdon exhibition at the Getty and is now director of the Frick Collection in New York. She recognized it from a sketch in an original catalog of the 1777 Salon while preparing the exhibition catalog.

|

|

Louise Brongniart Houdon 1667

|

Louise Brongniart Houdon 2227

|

|

Bust of Louise Brongniart, Jean-Antoine Houdon, French, c. 1777, marble.

In the turn of her head and her alert eyes, Louise Brongniart engages the viewer. Presented as a sweet, intelligent child, Louise was about five when sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon carved this portrait for her father, an architect and friend of the artist. Avoiding the empty sentimentality common in representations of children in the 1700s, he captured Louise's intelligence and liveliness. The youth of the sitter and the artist's naturalistic rendering lighten the formality of the bust, a format adopted from antique sculpture. One of the greatest portrait sculptors of the late 1700s, Houdon popularized the genre of child portrait busts.

Houdon made several copies and versions of this work. He probably made the first generation of this work, a terracotta model now in the Louvre, as a gesture of friendship to Louise's father, Alexandre-Theodore Brongniart. Louise's brother Alexandre Brongniart, who was also sculpted at the same time by Houdon, was a French geologist and mineralogist who served as the director of the Sèvres Porcelain Factory from 1800 until his death in 1847. Alexandre probably then commissioned the marble version. Two other marble copies, as well as a bronze version, still exist.

|

|

Bellona Pajou HS4743

|

Faun Holding a Goat Saly HS9013

|

|

Minerva (previously Bellona), Augustin Pajou, French, c. 1775-1785, marble.

Until very recently this sculpture by Augustin Pajou was identified as Bellona, the sister of Mars and Roman Goddess of War, depicted with a military helmet and usually a breastplate or plate armor, and either weaponry, a flaming torch (as here), or sounding the Horn of Victory and Defeat. Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom and sponsor of arts, trade, and strategy, was from the 2nd century BC onward the equivalent of the Greek goddess Athena, who was the virgin goddess of music, poetry, medicine, wisdom, commerce, weaving, crafts and magic. As Minerva was also Etruscan goddess of war, and Pajou’s sculpture strides forward to protect what has been determined to be allegorical representations of Painting, Sculpture, Music, Justice, and Medicine (the attributes of which lie at her feet), the title of the sculpture was changed from Bellona to Minerva.

Augustin Pajou's midsize marble statues were generally intended for wealthy collectors. Scholars believe this piece was originally owned by Duke Étienne-François de Choiseul, an important member of the French aristocracy and a collector of paintings and prints. Choiseul also had a predilection for refined cabinet sculptures, like Pajou's figure of Minerva, and owned at least two other works by the sculptor. Pajou's accomplished rendering of antiquity, very much consistent with Enlightenment taste in the late 1700s, undoubtedly appealed to Choiseul. The subject of the statuette aptly reflects Choiseul's love of art, his diplomatic skills, and his position as secretary of state for war under the French king Louis XV.

Faun Holding a Goat, Jacques-François-Joseph Saly, French, 1751, marble.

A sensual faun, a spirit of the wilderness with goatlike features, poses in classical contrapposto while he tenderly holds a goat that he has placed upon a tree stump. From this stump hang the faun's musical instruments, which, like his goatlike features, associate him with Pan, god of the pasture in ancient mythology, who loved music. The sculpture was inspired by two famous antique statues that the French artist Jacques-Francois Saly saw while studying in Rome: Faun with Kid, discovered in Rome in 1676 and now in the Prado, and the Satyr with Grapes and a Goat from Hadrian's villa. Saly first made a plaster model of the faun, which he submitted to the Académie Royale in Paris as the first step for Academy membership. He was then asked to execute a marble version. Made specifically to impress and demonstrate his skill, this marble Faun Holding a Goat is among the most exquisitely carved and carefully finished of Saly's works. On the basis of this sculpture, the Academy accepted Saly as a member in 1751, and he received the patronage of Louis XV, Madame de Pompadour, and Christian VII of Denmark.

|

|

Hope Nourishes Love Caffieri 2214

|

Hope Nourishes Love Caffieri 2220

|

|

Hope Nourishes Love, Jean-Jacques Caffieri, French, Paris, 1769, marble.

|

|

A young woman with a sensually curved figure and a lovely, gentle face represents Hope. With her traditional attribute of an anchor, she nurses a winged Cupid, personifying Love. A common figure from antique sculpture, he has dropped his bow and arrows below him on the rock as he reaches up to nurse. Jean-Jacques Caffieri was the last (and the most celebrated) member of a renowned family of sculptors. For this marble group, Caffieri adopted an elegant and decorative style perfectly suited to his subject matter, and inscribed the title of his marble on the base: Hope Nourishes Love.

Hope's nursing breast is a familiar symbol of sustenance and comfort. Allegories of love and friendship were favorite subjects in sculpture and painting around the 1750s, providing sculptors with a noble conceit that encouraged a contrast between the platonic ideals of love and its earthly, sensual elements. The sensual tone of this work is characteristic of the Rococo style fashionable at the French court of Louis XV. The only other known version of this composition is a terracotta model for the marble, which is now lost, that was exhibited at the Salon of 1769.

For donating his busts of actors and playwrights to the French national theater, Jean-Jacques Caffieri gained free entry for life. His habit of making casts from his marble sculptures and giving them to institutions was fortuitous, for many of Caffieri's marbles were lost in a fire in 1761. Belonging to the third generation of a family of sculptors and bronzeworkers who had come from Italy in the previous century, Caffieri was the younger brother of bronzeworker Philippe Caffieri. Jean-Jacques won the Prix de Rome in 1748 and spent four years in Rome studying ancient art. When he returned to Paris, he became Sculpteur de Roi to Louis XV. He made his name with a series of portrait busts of contemporaries like Madame du Barry and famous dramatists of the past.

|

Hope Nourishes Love Caffieri 3081

|

|

Judgement of Paris Nollekens 1615

Three Goddesses, Joseph Nollekens, English, 1773-1776, white Carrara marble.

These three marble statues representing Minerva, Juno, and Venus formed part of a Judgment of Paris group. The Neoclassical goddesses accompanied a figure of Paris, now considered to be primarily a pastiche from the 1700s, the figure of Paris was then believed to be a heavily restored Roman marble statue, with parts perhaps dating to the 100s AD. In the ancient Greek mythological story, Paris judged who was the most beautiful among the three goddesses. Although the figures have a cool remoteness, a powerful narrative engagement animates the group in a way rare for sculpture of the 1700s. Indeed, the artist's conception of using a room as a stage for the narrative recalls Bernini's dramatic Baroque compositions.

Although the depiction of the goddesses is in general quite traditional, Nollekens has shown each of them as if in a different stage of undress. The winner of the competition, Venus, the traditionally unclothed goddess of beauty, is shown in the process of removing her sandals. Juno, the goddess of marriage, bares one breast and is removing her dress. Minerva, the goddess of wisdom and warfare, has yet to put down her shield and only just begins to reach up as if to remove her helmet.

Charles Watson-Wentworth, second Marquess of Rockingham, commissioned the three statues from English sculptor Joseph Nollekens. As a testament to his classical education and the taste he developed during his Grand Tour of Italy at age eighteen, the marquess assembled this group and other works in his Neoclassical sculpture gallery. The group was designed for the marquess's London house, and after 1782, taken to his heir's estate at Woodhouse, near Rotherham in Yorkshire.

|

|

Juno Nollekens 1664

|

Juno Nollekens 3761

|

|

Juno, Joseph Nollekens, British, 1776, white Carrara marble.

Matronly Juno, goddess of marriage and queen of the gods in Roman mythology, bares one breast and undoes her dress for Paris's judgment of who among the three goddesses, Venus, Minerva, and Juno, was the most beautiful. This ample figure, crowned and heavily draped, stood with three other marble statues representing Venus, Minerva, and Paris.

Based originally on a Greek myth, the titles of these sculptures use the Roman equivalents. In the original Greek myth, Zeus held a banquet in celebration of the marriage of Peleus and Thetis (parents of Achilles). Eris, goddess of discord, was not invited as she would have made the party unpleasant. Angered by the snub, Eris arrived at the celebration with a golden apple from the Garden of the Hesperides, which she threw into the proceedings, upon which was the inscription "for the fairest one". Three goddesses claimed the apple: Hera, Athena and Aphrodite, and asked Zeus to judge which of them was fairest. Eventually, reluctant to decide, Zeus declared that Paris (a Trojan shepherd/prince) would judge, as he recently showed exemplary fairness in a contest in which Ares in bull form had bested Paris' own prize bull, and Paris unhesitatingly awarded the prize to the god.

|

|

Venus Juno Nollekens 2210

|

Venus Nollekens 1663

|

|

Venus, Joseph Nollekens, British, 1773, white Carrara marble.

Venus, goddess of beauty and love in Roman mythology, leans on a tree trunk to remove her remaining sandal. Turning inward, she draws the viewer in to examine her nude body. Carved fully in the round, the figure provides views from multiple angles.

With Hermes as their guide, the three candidates bathed in the spring of Ida, then confronted Paris on Mount Ida in the climactic moment that is the crux of the tale. While Paris inspected them, each attempted with her powers to bribe him; Hera offered to make him king of Europe and Asia, Athena offered wisdom and skill in war, and Aphrodite, who had the Charites and the Horai to enhance her charms with flowers and song (according to a fragment of the Cypria quoted by Athenagoras of Athens), offered the world's most beautiful woman, Helen of Sparta, wife of the Greek king Menelaus. Paris accepted Aphrodite's gift and awarded the apple to her, receiving Helen as well as the enmity of the Greeks and especially of Hera. The Greeks' expedition to retrieve Helen from Paris in Troy is the mythological basis of the Trojan War.

|

|

Venus Nollekens 3760

|

Venus Nollekens HS4694

|

|

Detail of the face of Venus, taken in natural light and mixed natural and artificial light (on different days).

Venus was the Roman goddess of love, beauty, sex and prosperity, and was the mother of the Roman people through her son Aeneas, who survived the Fall of Troy and fled to Italy. Julius Caesar claimed her as a direct ancestor through Aeneas. She was equated very early in the 3rd century BC with the greek goddess Aphrodite, and the rites in temples of Venus were influenced or based on cults of Aphrodite.

|

|

Minerva Nollekens 2206

|

Minerva Nollekens 3077

|

|

Minerva, Joseph Nollekens, British, 1775, white Carrara marble.

Goddess of wisdom and war, the stately Minerva stands like a majestic column as she raises her helmet. At her side rests a large shield, on which is carved the frightening head of Medusa, used to ward off enemies. Her body is composed in a spiral, which provides interesting views from several different angles. The image at left was taken in natural light, at right in mixed light.

Athena's beauty is rarely commented in the myths, perhaps because Greeks held her up as an asexual being, being able to "overcome" her "womanly weaknesses" to become wise and talented in war (both considered male domains by the Greeks). Her rage at losing makes her join the Greeks in the battle against Paris' Trojans, a key event in the turning point of the war.

|

|

Minerva Nollekens HS4643

|

Minerva Nollekens HS4657

|

|

Detail of Nolleken’s Minerva taken in mixed natural and artificial light. The natural light was low (stormy day).

Minerva was derived from the Etruscan Menrva, goddess of wisdom, war, art, schools and commerce. After the 2nd century BC, Romans equated Minerva with the Greek goddess Athena, the virgin goddess of music, poetry, medicine, wisdom, commerce, weaving, crafts and magic. Minerva was a complex goddess, and was worshipped as part of the Capitoline triad of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva (as the daughter of Jupiter).

Minerva Nollekens 3758

Detail of Nolleken’s Minerva taken in natural light.

Nolleken’s Three Goddesses and the Paris pastiche were originally placed on revolving mahogany pedestals to allow multiple viewing options. Minerva's shield has visible handles and her drapery falls over the oval rim, plus there are many other details of the three statues which indicate that they were intended to be viewed in the round. The Three Goddesses, and especially his Venus, were influenced by Nolleken's interest in the works of the Florentine Mannerist sculptor Jean Boulogne or Giambologna, and form one of the earliest important groups of English sculpture created for an English patron.

|

|

Apollo Canova 1661

|

Apollo Canova 1673

|

|

Apollo Crowning Himself

Antonio Canova, Italian, 1781, marble.

As Ovid told the story in his Metamorphoses, when the beautiful nymph Daphne finally escaped the pursuing Apollo when Diana transformed her into a laurel tree, the Roman god of music and poetry pledged his unrequited love: Although you cannot be my bride, you shall at least be my tree; I shall always wear you on my hair, on my quiver, O Laurel. In this marble, half-life-size statue inspired by this episode of the Metamorphoses, Apollo crowns himself with a laurel wreath. Nude except for sandals, his lyre hangs on the tree trunk that supports a piece of drapery. He stands in contrapposto, characterized by the opposition of straight and bent limbs, in a moment of reflection after the dramatic chase.

Apollo's nudity, his broad, muscular chest, and his relaxed, balanced pose all recall famous antique representations of the god. But while sculptor Antonio Canova clearly emulated several antiques, his Apollo is not a copy of an already existing statue. The commission for the marble was the result of a competition organized by Don Abbondio Rezzonico, nephew of the Venetian Pope Clement XIII, as a study in Classical pose and proportion in competition against a now lost figure of Minerva Pacifica by the well-established Neoclassicist sculptor Giuseppi Angolini. The size and the subject of Apollo must have been specified by Rezzonico, as Canova preferred and had a talent for life-size figures, and he never again produced half life-size marble statuette.

Antonio Canova was considered the greatest Neoclassical sculptor from the 1790s until his death in 1822, and was the most famous European artist of his time. Despite his reputation as a champion of Neoclassicism, his earliest works in Venice exhibited the characteristics of late Baroque and Rococo sculpture. This statuette of Apollo was Canova's first Roman work in marble and marked a crucial turning point in his career. Inspired by his first-hand study of ancient statues, Apollo exemplified the graceful style and idealized beauty that would become Canova's trademarks for the next forty years.

The image at right was taken on a dark and stormy day.

|

Apollo Canova HS9023

|

|

Apollo Canova 3759

Called "the supreme minister of beauty" and "a unique and truly divine man" by contemporaries, Antonio Canova was considered the greatest sculptor of his time. Despite his lasting reputation as a champion of Neoclassicism, Canova's earliest works displayed a late Baroque or Rococo sensibility that was appealing to his first patrons, nobility from his native Venice. During his first and second visits to Rome in 1779 and 1781, Canova reached a turning point. He studied antiquities, visited the studios of the Roman restorers Bartolomeo Cavaceppi and Francesco Antonio Franzoni, and came under the influence of the English Neoclassicist Gavin Hamilton. In the competition organized by Venetian aristocrat Don Abbondio Rezzonico, Canova produced his statuette of Apollo Crowning Himself, a work inspired by ancient art of a physically idealized and emotionally detached figure. This work came to define the Neoclassical style. The success of the Apollo enabled the young sculptor to obtain a block of marble for his next work on a large scale, Theseus and the Minotaur, which established his reputation. From the moment of its completion, it was the talk of Rome. From then until his death, Canova's renown grew throughout Europe.

|

|

Caracalla Cavaceppi 1660

|

Caracalla Cavaceppi 3076c

|

|

Bust of Emperor Caracalla, Bartolomeo Cavaceppi, Italian, Rome, c. 1750-1770, marble.

Caracalla, one of the most bold and brutal Roman emperors, ruled from 211-217 AD. He murdered his brother in his ascent to sole power and later was himself assassinated. In this bust, he wears armor and a military commander’s cloak. Tilting his head down and turning it to the left, he focuses on something which apparently does not meet with his approval. He flares his nostrils and furrows his brow, movements perhaps intended to suggest his ferociousness.

In the 1700s, Caracalla's likeness was known from a bust in the Farnese collection in Rome (then Naples) believed to date from the 200s. Bartolomeo Cavaceppi drew on this famous prototype for his marble bust of Caracalla. Carved during a period in which collectors bought sculptures all' antica, this bust was probably intended for an English collector's Neoclassical gallery. Cavaceppi was best known for his restorations of antique sculpture rather than for his rare original works, such as this one. He demonstrated his familiarity with classicism through his skillful drillwork in the antique manner, which is seen in the handling of Caracalla's beard and hair. This bust is one of Cavaceppi's rare signed works.

|

|

Caracalla Cavaceppi 2232

|

Caracalla Cavaceppi 3088

|

|

Caracalla was the nickname of Caesar Marcus Aurelius Severus Antoninus Pius Augustus, the oldest son of Septimius Severus (Emperor from 193 to 211). Born Lucius Septimius Bassanius in 188 in Lugudunum, Gaul (now Lyon), his titles included Britannicus, Parthicus, Arabicus, Germanicus and Adiabenicus Maximus (referring to subjugated peoples). His names refer to previous Emperors whom he was not related to (except Severus)... his father Septimius Severus was proclaimed Emperor by his legionaries during the political unrest following the death of Commodus, securing sole rule in 197 at the Battle of Lugdunum (Lyon, France). Caracalla got his nickname from the Gallic hooded cloak he wore (even to sleep in). Caracalla ruled jointly with his father from 198 until the death of Severus in 211, then with his brother Geta until December 211, when he had Geta assassinated in front of their mother by the Praetorian Guard (Geta died in his mother’s arms), then ruled alone until he was also assassinated by an officer of his personal bodyguard in 217, while relieving himself on the way to a Parthian campaign.

Bartolomeo Cavaceppi's signed Bust of Emperor Caracalla was one of several versions he created based upon an ancient model, the Farnese-type bust from 212-215 AD, which showed Caracalla in a lorica hamata (a type of armor with shoulder flaps similar to the Greek linothorax) and a paludamentum (a military commander's cloak or cape, fastened at one shoulder with a fibula), with a high, furrowed forehead, voluminous curls of hair, tense facial features, a scowling expression, and an exaggerated turn of his head to the left which contorted his neck. The Farnese-type bust was copied by a number of sculptors contemporary with Cavaceppi, no doubt due to its forceful evocation of ancient history, its apt portrayal of Caracalla’s reputation as one of the most ruthless of Emperors (notorious for persecutions and massacres which he authorized and instigated throughout the Empire), and its aesthetic appeal, which German art historian and archaeologist Johann Joachim Winckelmann ranked as being worthy of the famous Greek sculptor Lysippus.

Most of the work done by Cavaceppi was in restoring antique Roman sculptures and making casts, copies and fakes of antiques... fields in which he was the leading sculptor. For example, he restored the Tivoli-type head excavated in 1776 in the garden of the nuns at the Quattro Fontane for Charles Townley which is now in the British Museum (shown below), attaching the head to a marble bust he created to match it and blending the seam in an expert repair. In the Townley bust, he attached the head in a more frontal position, and the chest and shoulders he created for the head differ in the drapery and truncation of width and height from some of the other Tivoli-type busts.

|

|

Caracalla Cavaceppi 3700

|

Caracalla Cavaceppi HS9027

|

|

Cavaceppi was obviously proud of this original portrait, as he rarely signed his copies of antique sculptures. This bust may have been the one which was in his personal collection when he died (it does fit the description). The deep drill work and carving of the hair and beard create dramatic contrasts with the smooth surfaces of the face and neck. This would seem to place the date of this bust in his earlier period, before 1760, as his later works exhibited shallower modeling and less polished or fine-matte surfaces, but there is no documentation on the dating of this bust (thus the wider date range, from 1750-1770).

The prototype for Cavacetti's marble and similar copies has traditionally been identified as the bust owned by Cardinal Alessandro Farnese, which gained a reputation (which lasted for centuries) as the most beautiful example of this portrait type, and was considered by 18th century antiquarians as the archetypal antique representation of Caracalla. It stood in the Palazzo Farnese in Rome in the 16th and 17th centuries, then part of the collection was moved to Parma by Antonio Farnese (Duke of Parma). When he died in 1731, the Farnese collection was transferred by Elisabetta Farnese, wife of Philip V of Spain, to their son Charles of Bourbon, who became King of Naples in 1734. He moved the Parmesan collection to Naples. The remainder of the Roman Farnese collection (including the Farnese Caracalla) was moved to Naples by his son, Ferdinand IV in 1787. The Farnese Caracalla is now in the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli. Some scholars contend that Cavaceppi may have used the similar bust in the Vatican collection, as he was the primary restorer of antiquities for Cardinal Albani and the Pope. When he died, Cavaceppi did have a plaster cast of a Caracalla bust that is assumed to have been taken from the Vatican bust.

|

|

Caracalla British Museum 1033 M

Caracalla, Tivoli-type bust, Roman, 215-217 AD, marble.

An example of the Tivoli-type of bust (named after Hadrian's Villa at Tivoli, where one of them was found), this is a gentler description of Caracalla with a more naturalistic technique and a reduced volume of hair, from the period when he was the sole ruler of Rome between 215-217 AD. The earlier Farnese-type busts from 212-215 AD showed an exaggerated contraction of the forehead and a contorted neck (this was just after he had his brother and co-Emperor Geta murdered by members of the Praetorian Guard). This bust, showing the Emperor draped in a paludamentum over armor with his head turned slightly to the right, was excavated in the garden of the nuns at Quattro Fontane on the Quirinal Hill in Rome in 1776, and was purchased by Charles Townley after the head was mounted on a modern body by Cavaceppi. It was acquired by the British Museum in 1805.

|

|

Risamburgh Family Chinard 2218

|

Risamburgh Family Chinard 3082c

|

|

Allegorical Portrait of the van Risamburgh Family, Joseph Chinard, French, 1790, marble.

Carved out of a single block of gleaming white marble, this allegorical portrait represents the Van Risamburgh family in a sweet and affectionate commemorative portrait. Lovingly looking down, Madame van Risamburgh, dressed as Minerva, goddess of wisdom and war in ancient mythology, raises her shield as a canopy over her languidly slumbering young son. He is improbably perched on a pile of military equipment and holds a sword or dagger that is clearly too large for him in his right hand. Monsieur van Risamburgh, a prominent Lyon merchant, is represented by his profile medallion portrait on a shield at the base. The medallion format, traditionally used for tomb monuments, implies that, although still living, he is absent from the family. Through the use of allegory, sculptor Joseph Chinard suggested that Madame van Risamburgh was protecting her son from the civil and military unrest of the French Revolution while her husband was away, possibly engaged in military or civic duties.

|

|

Risamburgh Family Chinard HS4730

A popular Neoclassical artist, Chinard drew on ancient mythology and used classical forms but imbued the work with a very contemporary emotional feeling, celebrating family life as the source of happiness. This sculpture is the first family group by Chinard in which the presence of a living but absent father is conveyed by means of a portrait medallion, a device cleverly adopted from traditional tomb monuments. With its highly detailed still life of weaponry, softly modeled anatomy, and elegantly arranged, transluscent folds of drapery, the Van Risamburgh Family is arguably Chinard's most beautifully carved marble.

Joseph Chinard trained early as a painter, then worked with a local sculptor in his native city of Lyon. His work drew a patron, who sent him to Rome (1784-87), where he made copies of antiquities and sent them back to Lyon. While in Rome, he received a rare honor for a non-Italian, a prize from the Accademia di San Luca for his terracotta Perseus and Andromeda. When he returned to Rome in 1791, he drew the ire of the Catholic Church and was imprisoned in the Castel sant'Angelo when his terracotta of the base of a candelabrum in which Apollo trampled Superstition was considered subversive by the Pope. Later, upon his return to Lyon, he made family allegories and other intimate terracotta and marble portraits, some of which are below.

|

|

Marine Scene Opstal 1730

Marine Scene, Gerard van Opstal, Flemish, Flanders or Paris, c. 1640, alabaster.

In a tumultuous, windblown scene, five bearded fishermen and six winged putti haul a bursting net of fish aboard their boat. One in a series of five relief panels portraying marine scenes, this panel was probably created as part of an ensemble for a state or municipal building with a maritime function.

The men's strenuous exertions and the representation of the wind's effects imbue the piece with vitality. Although the stomachs of the putti protrude in the voluptuous curves of high relief, the fishermen's larger muscular figures form a lively series of curves in low relief. The viewer's eye traces over their curved backs and follows their billowing clothing, experiencing the movement of these struggling figures. Reinforcing the action, the Flemish artist Gerard van Opstal carved the alabaster into small planes that constantly shift directions. These planes break up the surface's solidity and give the work a flickering, watery quality akin to Peter Paul Rubens's effects in paint (van Opstal was strongly influenced by Rubens). This technique is similar to that used for carving smaller-scale works in ivory and boxwood, materials with which van Opstal was trained.

Gerard van Opstal was a Flemish Baroque sculptor who trained in Brussels under Niklaas Diodone. He moved to Paris in 1648 after being invited by Cardinal Richelieu, and became one of the founders of the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture. He was awarded the title 'sculpteur des batiments du roi' (sculptor of the king's buildings) in 1651. Gerard van Opstal was particularly skilled in the carving of low-relief friezes with classical mythological themes. He worked in stone and marble, and was also an expert in carving ivory reliefs, which were widely admired and collected by his contemporaries (Louis XIV had 17 ivories by van Opstal in his collection). His style combined elements of Roman sarcophagi, the Renaissance, the Baroque styles of Peter Paul Rubens and Francois Duquesnoy and the emerging French classical style.

|

|

Venus Reclining Deare HS4687

Venus Reclining on a Sea Monster with Cupid and a Putto, John Deare, English, 1785-1787, marble.

Venus, the goddess of love and beauty, reclines on a fantastic goat-headed sea monster in this allegory of Lust, based on the medieval representation of a woman riding a goat. The goddess entwines her fingers in the creature's beard (a traditional gesture representing erotic intent) while the monster licks her hand in response. Cupid, astride the monster's long serpentine tail, is poised to shoot an arrow at Venus, while in the background a putto adds to the amorous imagery by holding a flaming torch, undoubtedly meant to suggest the burning ardor of desire. The sea goat carries Venus through the frothy waves, carved with energy and precision characteristic of Deare’s technique in high, medium and low relief.

John Deare displayed his great skill in carving a variety of levels and textures in this sculpture, from the low relief of the Cupid and putto to the smooth, half-relief of Venus, and finally to the sea-goat's fully three-dimensional snout and wavy strands of hair. Deare's depiction of Lust as a woman riding a goat forms part of an iconographic tradition that has been popular since the Middle Ages. He signed the relief “John Deare made it” in Greek instead of the usual Latin.

|

|

Venus Reclining Deare HS4717c

John Deare was one of the most innovative and accomplished British sculptors who worked in the Neoclassical style. In 1780, only four years after beginning his apprenticeship under Thomas Carter, he became the youngest artist to win the Royal Academy's Gold Medal. Deare went to Rome in 1785 to study ancient sculpture, and produced his own works there, achieving great success in his specialty (relief sculpture), which were especially popular among the British making the Grand Tour (even the great Canova praised his work). His early death was caused by purposely falling asleep on a block of marble for inspiration.

|

|

Maria Cerri Capranica Algardi 2416

Bust of Maria Cerri Capranica, attributed to Alessandro Algardi, Italian, c. 1640, marble.

Befitting a young noblewoman, Maria Cerri Capranica is dressed in a velvet gown with an elaborate lace collar. Her elegant outfit is complemented by an array of jewelry--a long strand of pearls, a necklace set with precious stones, a pendant with a small relief of the Holy Family, and pearl drop earrings. The sitter was clearly a woman of status and affluence, and the sculptor depicted her with a powerful and distinctive psychological presence.

The fine details of the sitter's costume, jewelry, and hairstyle display a true mastery of marble carving. Maria Cerri's intricate coiffure--a mass of curls ornamented with loops of satiny ribbon--falls gracefully around her face. Algardi sculpted the delicate lace mantle in low relief with subtle contours that reveal how the garment fell around the sitter's shoulders. The strand of pearls, which weaves across the sitter's chest and around her sash, is carved entirely in the round. The attention given to her lace and jewelry makes this as much a portrait of her accessories as of the subject herself.

Married in 1637, Maria Cerri and Bartolomeo Capranica were from prominent Roman families. A coat of arms identifying both families appears at the base of the sculpture. Maria Cerri died at the age of twenty-five in 1643.

|

|

Maria Cerri Capranica Algardi HS9249

|

Mary Robinson d’Angers HS4706

|

|

This bust of Maria Cerri Capranica was once owned by William Randolph Hearst, and was acquired by the Getty in 2000, when it was called Bust of a Noblewoman and mistakenly IDed as Isabella Celsi Capranica based on the coats of arms of Capranica and Celsi, the only member of both families being Isabella. Based on research in the 1950s it was attributed to Giuliano Finelli, GianLorenzo Bernini’s chief assistant.

In a 2011 paper for Sculpture Journal, Andrea Bacchi and Catherine Hess traced the provenance of the sculpture and suggested that it should be attributed to Algardi rather than to Finelli. In 2003, based on the similarity of the socle (pedestal) to Algardi's bust of Maria Cerri Capranica's father Antonio Cerri, it was determined that the coat of arms was not Celsi, but Cerri. (The coats of arms are similar: celso = mulberry tree; cerro = turkey oak). Once the subject of the bust had been determined, it became obvious that Finelli could not have carved it because he left Rome in 1634, three years before Maria was married. Further evidence was discussed, including the figural pendant being a relief produced in Algardi's workshop, the similarity of lace details, and the carving of the hair and ribbons to several busts known to have been done by Algardi. The detailed analysis concluded that this bust must have been done by Algardi. In 2012, the Getty agreed and reattributed the bust. As has been seen on these pages, it is sometimes difficult to properly identify the artist and the subject without supporting documentation.

Bust of Mary Robinson, Pierre-Jean David d'Angers, French, 1824, marble.

This austere bust of a young American woman by a French sculptor has an enigmatic air. The lack of accessories, the geometric simplicity of the shapes, and the classicizing square form of the bust give the work an otherworldly effect. To augment this effect, the artist carved the face with smooth planes, left the pupils blank and unincised, and fashioned the large loops of hair on the top of her head in simple, clear shapes to bring out the figure's abstract qualities.

The figure's remote classicism is leavened by the naturalism of details such as her bumpy nose. Pierre-Jean David d'Angers captured the awkwardness of adolescence in his sitter, representing Mary Robinson as a shy teenager with her head demurely tilted forward and down, casting a deep shadow below her brows. Mary Robinson was the daughter of a merchant and sea captain with a route between New York and Le Havre, France. She probably sat for the sculptor on a family visit to France.

|

|

Mary Seacole Weekes 2263

Bust of Mary Seacole, Henry Weekes, British, 1859, marble.

Mary Seacole, the subject of this bust, looks out with an expression revealing the intelligence, compassion, and strength for which she became known in Victorian England. An extraordinary Jamaican woman of mixed race, Mary Seacole traveled extensively in Central and South America, where she gained valuable experience in treating yellow fever and cholera. When the Crimean War broke out in 1854, she tried to obtain a position with a British nursing unit but was rejected several times, so she followed the troops as a sutler, one of the many people offering hospitality services and running inns, bars, and restaurants. In the Ukraine, in addition to running a hotel, she supplied daily medical services to British troops on the front line, remaining even longer than her fellow nurse Florence Nightingale.

After the war, Seacole published her autobiography, The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands, which became a huge popular and commercial success. By the time Henry Weekes executed this bust in 1859, she was a household name in England. Emphasizing her innate nobility, Weekes used a simple oval form for the chest, adorning the mature woman with only a necklace and the hoop earrings that she always wore. The unusual socle covered with palm leaves refers to Seacole's Jamaican origins, considered tropical and exotic by the English.

Henry Weekes established himself primarily as a portrait artist and held the position of Professor of Sculpture at the Royal Academy in London from 1868-1876. His bust of Seacole was a departure from his normal Neoclassical work and is considered to be his most imaginative portrait by far, combining the naturalistic and the fantastical. The face is realistically modeled, recording every nuance in the flesh, and the thick hair is gathered back in a snood, a contemporary accessory. At the same time, the head and chest seem to sprout from a cluster of gently curving palm leaves that effortlessly bear the weight of the marble. The innovative, whimsical design and the masterful carving make this one of Weekes’ most accomplished works.

|

|

Head of a Man Meit 1830

|

Head of a Man Meit 3247

|

|

Head of a Man (possibly Cicero), attributed to Conrat Meit, German, France or Netherlands, c. 1515, alabaster.

The stern-faced man looking slightly off to his right with noble bearing strikes the viewer with his forthrightness and candor. The deep crow's feet, creased forehead, and sagging skin suggest a mature age, while his modest, short-cropped hair and the lack of ornamentation speak of a stoic conservatism. Above all, the representation establishes the sitter's moral authority. The distinctive mole at the corner of the left eye suggests that the subject is Marcus Tullius Cicero, the famous Roman orator, statesman, lawyer, and poet. According to the Roman historian Plutarch, Cicero's name derived from a description of the mole in Latin as cicer, or chickpea, a feature of the subject which became standard in Renaissance depictions.

|

|

Head of a Man Meit 3957

German Renaissance sculptor Conrat Meit carved the Head of a Man as an all’antica emulation of busts from the Roman Republican period; with unmarked eyeballs and forward-combed hair resembling strands of spaghetti. The starfish pattern on the back of the head is also typical of ancient busts. This kind of bust, which has been reset on a modern support, would have probably decorated the interior of a noble residence.

Conrad Meit became official court sculptor in 1514 to Margaret of Austria (only daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I), who was the Duchess of Savoy and regent of the Netherlands. Among other works, Meit created the monumental effigies in the tombs of Margaret of Austria, Philibert II, Duke of Savoy (who died at 24), and Philibert's mother, Margaret of Bourbon in the Royal Monastery in Brou. These tombs, along with the boxwood busts of Philbert of Savoy and Margaret of Austria and a signed alabaster statuette of Judith with the Head of Holofernes, provide a secure foundation for attribution of works to him.

|

|

Bust of Winter Heermann 1710

|

Bust of Winter Heermann 1711

|

|

Bust of Winter, Paul Heermann, German, c. 1700-1732, marble.

Shrouded in a heavy hooded cloak, an elderly man looks down with a deeply furrowed brow. As a personification of winter, the bust gives visual expression to the chilling cold of that season. His old age refers to winter's occurrence at the very end of the calendar year. Paul Heermann used delicate drillwork to create the border and ruffle on the cloak and the undercut locks of his long beard. The shadows made by his protruding forehead and the folds of his hood contrast dramatically with the luminous white of the marble, heightening the figure's psychological force and presence. This bust was probably part of a series of sculptures personifying the four seasons. The high level of finish and finely worked details of this bust suggest that Winter was meant to be viewed up close, in an indoor setting.

|

|

St. Gines de la Jara Roldan 1836

|

St. Gines de la Jara Roldan 4037

|

|

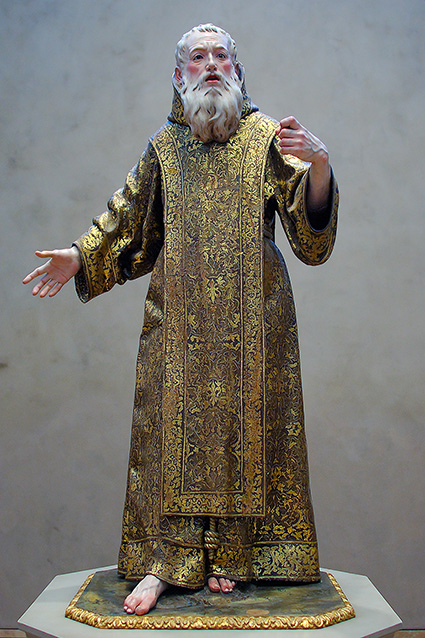

Saint Ginés de la Jara, Luisa Roldán, Spanish, c. 1692, polychromed wood (pine and cedar) with glass eyes.

The statue of St. Ginés de la Jara challenges the boundaries between art and reality. Life-sized, carved and painted to resemble a living human, and dressed in a brocaded robe made of wood which seems to have the qualities of fabric, this startling sculpture displays the appearance of truth characteristic of the Spanish Baroque. The effect is heightened by the actions and expressions of the saint, who is stepping forward, looking towards his left, and appearing to speak. He probably once held a staff in his left hand. Various legends both in France and Spain describe how St. Ginés (or St. Genesius depending on the location), who was either descended from French royalty or a kinsman of Roland who refused any claim to the French throne (which explains the fleur-de-lys, emblem of the kings of France, in the pattern of the robe), came to be venerated in the Murcia area near Cartagena, Spain known as La Jara (or La Xara). The most spectacular legend states that after Ginés was decapitated in southern France, he picked up his head and threw it into the Rhône River, where it floated into the sea and was washed up on the coast of Murcia, which became the center of his cult.

When the museum acquired the statue in 1985, it was misattributed to José Caro due to a misreading of the partially legible signature on the base, which seemed to make sense at the time because José Caro was active in the area of Murcia. After comparing surviving works by Caro to the statue, it became clear that the statue was not sculpted by Caro. Mari-Tere Alvarez at the Getty questioned the attribution and reanalyzed the signature, interpreted the inscription as reading Luisa Roldan, then compared the statue of St. Ginés to other surviving works of the court sculptor Luisa Ingnacia Roldan, known as La Roldana, determining that the gilded motif on the base of St. Ginés was identical to other, signed pieces by the artist.

Luisa Ignacia Roldán (1652-1706), called La Roldana, was a Spanish Baroque sculptor and the first woman sculptor documented in Spain.Daughter of the sculptor Pedro Roldán and trained at his hand, she created wood sculptures for the Cathedral of Cadiz and the town council. Designated court “sculptor to the bedchamber” (escultora de cámara, which was part of the signature) in 1692 by Charles II, La Roldana probably produced St. Ginés as a royal commission. The figure was polychromed by her brother-in-law, Tomás de los Arcos, who used the Spanish technique of estofado to replicate the brocaded ecclesiastical garments. In this process, the area of the figure's garment was first covered in gold leaf and painted over with brown paint, and then incised with a stylus to reveal the gold underneath. Saint Gines is the artist's only known verifiable wood sculpture outside of Spain.

La Roldana has masterfully carved Saint Ginés. She has depicted the hands and neck in great detail, sculpting the veins and bones so they are dramatically pronounced beneath the skin. The nose is straight with a little lift at its end that accentuates the lip area. The curved rims of the eyelids project outward, and the facial features are soft. The delicate eyes, the knitted brows, the rosy cheeks, the firmness of the feet, and the slight opening of the mouth are all similar to those of The Archangel Michael Fighting the Devil, also created in 1692 by La Roldana, now at El Escorial in Spain. Only a few polychromed wood statues by La Roldana survive today, and the most notable of these are all from her period as royal sculptor. St. Ginés is absent from royal inventories taken at the time of Charles II's death in 1700, which raises the possibility that it was commissioned as a gift for one of his royal convents or monasteries, such as the Monastery de St. Ginés de la Jara.

|

|

Christ Child Polychrome Wood 1677c

|

Christ Child Polychrome Wood 3802

|

|

Christ Child, Italian, Genoa, c. 1700, Polychromed wood with glass eyes.

With cherubic red cheeks, elaborate curls, and folds of baby fat, the polychromed life-size wood statue of the nude Christ Child balances on a rocky landscape in an animated contrapposto stance, his cape billowing around his shoulders, and extends his left hand as if to display an object. In his hand he may have once held a globe referring to his role as Salvator Mundi, the Savior of the World, or possibly grapes, a Eucharistic reference. The right hand is bent inward towards his ear, suggesting that he is listening to the prayers of the beholders. The nude Christ Child was a popular subject in European wood sculpture beginning in the 1300s. Theologians of this period understood Jesus's nudity as a sign of his human nature. During the 1500s and 1600s, Saint Ignatius Loyola and Saint Anthony of Padua further encouraged devotion to the humanity of Christ. This figure is a high Baroque version of the popular theme, full of animation and theatricality.

|

|

Christ Child Polychrome Wood 1677

The fully carved-in-the-round statue was probably designed as a devotional image for an oratory, chapel, or church. It may also have been carried in religious processions or other spectacles of civic life, which were often staged by confraternities in Genoa on Feast Days, animated by vivid polychrome wood sculptures which were carried on floats.

When acquired by the Getty in 1996, the Christ Child was attributed to Anton Maria Maragliano, a Genoese wood sculptor who created many processional sculptures for confraternities. The depiction of the child is similar to sculptures of angels and putti by Maragliano, but a recent thorough photographic survey of his work by Daniele Sanguineti demonstrated that face and body details are distinctly different from children carved by Maragliano, and that the sculpture could not be his.

The general similarities to his work and the display of the sculptor's awareness of Baroque ideals (especially the animated windblown drapery) indicate that this work may have been carved in Genoa in about 1700. The cloak and the spiraling curls are nearly identical to those shown in works by the Genoese artist Filippo Parodi, but there are also similarities in the curls and the mouth to an 18th c. Christ Child possibly made in Naples. For now, the artist remains unknown.

|

|

St. Bartholomew 3697

|

St. Bartholomew 3072

|

|

Saint Bartholomew, Belgian, 1700s, terracotta.

Holding a swath of cloth around his lower body that reveals the aged skin of his chest, the elderly Saint Bartholomew intently gazes off into the distance as if having a vision. He clutches a book tightly, while his attribute of flayed skin rests behind him on a stump. The skin refers to his martyrdom: Saint Bartholomew was flayed alive and beheaded on an evangelical mission to the East. Thus, tanners and artisans who worked with animal skins venerated Saint Bartholomew, making him their patron saint.

This terracotta may have been created as a model for a larger-scale statue in stone or wood, possibly for a series of apostles, such as those that often decorate the nave or the choir stalls in Belgian churches. When this statue was acquired in 1994, it was attributed to the 18th century French sculptor Edme Bouchardon's and assumed to have been a preliminary, rejected model for the sculpture of St. Bartholomew as part of the commission for 24 life-size stone statues for the church of Saint-Sulpice in Paris. While the stone sculpture of St. Bartholomew does not look like this terracotta, the pose, the drapery and the handling of facial and anatomical features exhibit similarities to two of Bouchardon's Saint-Sulpice apostles (St. Andrew and St. Peter). This attribution has since been retracted, changed to an unknown Belgian sculptor. I can find no information that explains this change, but we have seen that attribution of artist, nationality, location, and even the subject of some of these works can be problematic.

|

|

Offering to Priapus Clodion 1655

|

Offering to Priapus Clodion HS9035

|

|

Offering to Priapus, Claude Michel (Clodion), French, c. 1775, terracotta.

In the history of European sculpture, the French Rococo artist Clodion is perhaps the most famous modeler of clay. During the nine years he studied in Rome (1762-1771), the renown of his terracotta sculptures became so great, his earliest biographer recorded that his works were "bought by amateurs even before they were finished". Among his clients was Catherine II of Russia (Catherine the Great), who attempted (without success) to attract Clodion to her court. Clodion capitalized on a growing interest in terracottas as objects to be collected, and his technical brilliance encouraged their aesthetic appreciation as independent works of art (rather than simply as sketches or models for works to be completed in more permanent media like stone or bronze). The subject of this work was originally considered to be a Vestal Presenting a Young Woman at the Altar of Pan when it was acquired by the Getty in 1985, but it was later determined that this term (bust on a pillar) had to be a representation of Priapus due to Cupid covering the monumental erection characteristic of the son of Aphrodite and Dionysus.

A woman dressed as a priestess leads a young girl, covering herself with a swath of cloth, toward a statue of Priapus, the ancient god of fertility. With distinctive goatlike ears, Priapus appears in the form of a term, a statue marking a territorial boundary. The smoking incense and the sacrificial tripod indicate that the term is an altar and the young girl is making an offering of her charms as an initiation rite to love or marriage. Cupid, whose bow and arrows lie on the ground below him, winds a floral garland around the statue of Priapus, camouflaging his characteristic erect phallus.

Sculptor Claude Michel, called Clodion, frequently drew from ancient mythology for his terracottas, but he rarely focused on grand events, preferring non-serious scenes with mythological figures of secondary rank. Clodion also typically contrasted a grotesque male figure (as Priapus certainly was) with a pretty female. For Clodion, ancient culture provided a classical figure style, a repertory of characters and settings, and perhaps most importantly, a nostalgic mood. As was typical of the Rococo style, his works tended to be playful and erotic. Although Clodion finished the piece in the round, he designed it to be seen from the front, placed on a piece of furniture or on a mantelpiece. Known for his masterful handling of wet clay, the artist focused on texture, differentiating clingy or billowing drapery from satin-textured skin.

|

|

Python Killing a Gnu Barye HS4636

Python Killing a Gnu, Antoine-Louis Barye, French, 1834-1835, red wax and plaster.

A large python wraps his winding body tightly around the straining gnu, forcing the much larger animal to the ground and biting him on the throat. The two beasts intertwine in a tangle of struggling legs and snake coils. Sculptor Antoine-Louis Barye posed the animals in contradiction to their natures: the light-footed gnu, whose delicate legs skip over rough surfaces, here is brought to the ground by the powerful constriction of the snake on its chest and spine, while the snake, whose lack of legs naturally forces him to shimmy along the ground, strikes the gnu's throat in mid-air. The pose of the gnu with its head stretched back and its mouth open, nostrils flaring as it gasps its last breath, adds pathos to this violent theme. Images like this one of a dramatic and ultimately Romantic struggle between life and death made Barye one of the most popular animal sculptors of the 1800s.

Barye was the greatest sculptor of animal bronzes in the 19th century, as well as an accomplished draftsman, a leading watercolorist, and a member of the Barbizon school of landscape painters. His work in each of these media is characterized by his scientific observation of natural forms and often emphasized the violent and predatory aspects of his subjects, placing him firmly within the French Romantic movement of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. His intense study of animals in captivity at the Jardin des Plantes zoo and skeletons at the Natural History museum, as well as his attendance at numerous lectures and his study of zoology and animal anatomy allowed him to render accurately the movements and musculature of his subjects. Barye elevated the status of the animal bronze to the level of more traditional subjects.

Made out of plaster retouched with red wax, the sculpture is a model for one of nine bronze groups of struggling animals commissioned by Ferdinand-Philippe, duc d'Orléans. The animal groups, which took Barye five years to complete, were composed of five hunting scenes and four animal combats, including the Python Killing a Gnu. They were designed as part of a large and elaborate table centerpiece for the Palais de Tuileries that was never completed. A bronze version of the wax model of the Python and Gnu is now in the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore.

|

|

Family of General Duhesme Chinard 1654

The Family of General Philippe Guillaume Duhesme, Joseph Chinard, French, Lyon, c. 1801-1805, terracotta.

With a melancholy air, an elegant woman and her young son contemplate a medallion portrait of an absent husband and father. While the affectionate child nuzzles his mother's arm, she props up the medallion on her elegant Empire style daybed. Sculptor Joseph Chinard paid great attention to stylish details such as elegant furniture and the woman's hairstyle and dress. Although he included such popular artistic conventions as a revealed breast, he also expressed her deep longing through her gentle manner and intense look. To make this love theme explicit, the artist used symbolic props such as the putti on the sides of the bed. The putto on the right represents earthly or sensual love, while the one on the left, with his eyes bound shut, represents heavenly or spiritual love. Together they hold the rope that symbolically binds the family together.

Chinard created this keepsake for the French Duhesme family, using a format traditionally reserved for tombs, where the medallion identifies the deceased. Since the figure represented in the medallion, General Philippe Guillaume Duhesme, was still living when this sculpture was made, the medallion signifies absence rather than death.

|

|

Family of General Duhesme Chinard HS9039

Joseph Chinard was the leading French Empire sculptor (the Empire style was the second phase of Neoclassicism from 1804 to 1814 in France, and until 1820 in other some countries), and after Antonio Canova, was the preferred sculptor of Napoleon and the Bonaparte family. Chinard established the image of the portrait medallion which permeated French art throughout the 19th century. The Family of General Duhesme is characteristic of Chinard's sculpture in its use of Classical composition and forms t provide a framework for detailed rendering of contemporary fashion and infusing storytelling elements into portraiture.

|

|

Madame Recamier Chinard 1573

|

Madame Recamier Chinard 1577

|

|

Bust of Madame Recamier, Joseph Chinard, French, c. 1801-1802, terracotta.

Coyly looking down, Madame Recamier holds a veil across her chest. The sheath both demurely conceals and reveals her breasts. Sculptor Joseph Chinard cleverly compensated for the artificiality of the bust form by elongating the bust to mid-torso and covering the transition between the body and pedestal with drapery, creating a work of surprising naturalism. The softly modeled limbs and the slight twists of her head and shoulders suggest a living presence while the upswept hairstyle suggests Recamier's elegance.

|

|

Madame Recamier Chinard 1597

|

Madame Recamier Chinard 3757

|

|

Juliette Récamier was celebrated in French Empire society for her beauty and love affairs. Married at fifteen to a wealthy lawyer whowas rumored to have been her natural father, she had a loveless, unconsummated marriage and carried on numerous flagrant affairs, the most celebrated with the Prussian Prince Augustus, the youngest brother of King Frederick II. In her Parisian townhouse, she held a fashionable literary salon frequented by the political and educated elite. Some of the most accomplished portraitists of the era sculpted, drew, and painted her image. Chinard's terracotta bust, considered one of the most successful at capturing her spirit and beauty, was produced in several different versions in both clay and marble.

|

|

Madame Recamier Chinard 1603

|

Madame Recamier Chinard 1612

|

|

I have provided several angles of this magnificent bust, taken in different light.

Juliette Récamier became one of the most sought-after women in Paris in spite of her married status. She was like a modern super-celebrity... an appearance in public incited huge crowds, who jostled to get a glimpse of her. Her appearance embodied the fashionable Neoclassical taste: her coiffure was inspired by ancient Roman frescoes, she wore only white flowing garments, and she had a reputation as a coquette, even though she remained a virgin until age 40.

|

|

Madame Recamier Chinard 1581c

|

Madame Recamier Chinard 2245

|

|

Juliette Récamier was good friends with (and a constant host to) a number of former royalists at a time when being alienated with the French government was dangerous. This, along with her refusal to act as a lady-in-waiting to Empress consort Josephine (wife of Napoleon Bonaparte) brought her under suspicion. Her political equivocations eventually got her exiled from Paris by Napoleon, and she traveled to her native Lyon, then on to Rome, Naples and Switzerland, where she became involved in the Bourbon intrigues of Joachim Murat and his wife, Caroline Bonaparte (Napoleon's younger sister). She was finally able to return to Paris after Napoleon lost power. She retired to a convent in 1819, but still received visitors in her apartment there.

|

|

Madame Recamier Chinard 1656

|

Madame Recamier Chinard 3068c

|

|

This terracotta was Chinard’s model for the marble bust he carved in 1804, which is in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon. Chinard made several other terracotta and marble busts of Juliette Récamier in various styles, some derived from this bust and some more demure. In this terracotta, Chinard captured the beauty and charm which attracted so many to Madame Récamier.

|

|

Self Portrait as Midas Carries 3909

|

Self Portrait as Midas Carries HS9672

|

|

Self-Portrait as Midas, Jean-Joseph Carriès, French, probably 1885, patinated plaster.

The unusual feature of donkey's ears provides the clue to the identity of this disembodied head of an older man, with closed eyes and tilted to the side. He represents the mythological King Midas, a figure of legendary foolishness best known for a magical touch that turned all objects to gold. According to Ovid's Metamorphoses, Apollo punished Midas by giving him the ears of a donkey after he chose Pan rather than Apollo in a musical contest.

Jean-Joseph Carriès left the head oddly truncated, resting not on a torso nor even on a neck but rather on a mass of roughly handled plaster. This amorphous truncation expresses the inner spirit divorced from bodily form. As a self-portrait, the image forms an allegory of Carriès's life. Perceiving himself as foolish, bestial, and uncultured, he presented a thoroughly modern, powerfully intimate, yet ultimately debased representation.

One of his most celebrated works (also called the Sleeping Faun), Carriès formed this head with plaster in a many-pieced mold, then shellacked it to give it a patina resembling metal. He also made other versions in plaster, wax, clay, and bronze. Carriès was also a noted perfectionist, and when he met Pierre Bingen, a bronze founder specializing in the Renaissance method of lost-wax casting which faithfully reproduced the plaster model, he worked together with him closely, designing his own patina for the bronze. Carriès’ work mingled naturalism and symbolism, and he was a highly admired sculptor in the late 19th century.

|

|

Vexed Man Messerschmidt HS8994c

The Vexed Man, Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, German, Austria, 1771-1783, alabaster.

The Vexed Man is one of a series of 69 "character heads" made by Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, an eighteenth century German sculptor active in Austria. Messerschmidt sculpted them during the last thirteen years of his life, while apparently suffering from an undiagnosed mental illness.

Resembling the ventriloquist Jeff Dunham’s puppet Walter, the Vexed Man by Messerschmidt portrays a middle-aged man with a sour expression, which seems to fall somewhere between a grimace and a scowl. The most telling aspect may be the furrowed brow above squinting eyes and a scrunched nose. But natural cracks in the bust's alabaster surface seem to echo the topography of his skin, both softened by age yet hardened by the extreme expression. The man's receding hairline, wrinkles, and sagging jawline contrast with tensed cheek and neck muscles. Although the character seems to express irritation and annoyance, it is not certain whether Messerschmidt intended that interpretation, because he did not give the bust a title.

|

|

Vexed Man Messerschmidt HS8998

|

Vexed Man Messerschmidt HS9629

|

|

This bust and the series it belongs to reflect the intellectual concerns of artists and scholars during the Enlightenment era, when a surge of interest in the sciences occurred. Studies in physiognomy were highly popular at the time. Perhaps as influential was Messerschmidt's undiagnosed mental condition, which could have been schizophrenia, possibly caused by casting sculptures with poisonous tin alloys. A contemporary wrote that he was told by Messerschmidt that by making the character heads, he hoped to ward away spirits that invaded his mind.

Franz Xaver Messerschmidt mastered the art of capturing extreme human expression during the mid-18th century, claiming to catalog what he counted to be a range of 64 human expressions. In his time, intellectuals were interested in what the external aspects of a person could indicate about the internal, and several sciences, such as physiognomy and pathognamy, were dedicated to judging a person’s mind based on their appearances. As such, the comical and theatrical depictions of the human face made Messerschmidt famous.

|

|

Vexed Man Messerschmidt HS9639

This bust is unusual in more than its portrayal of expression... alabaster was a very rare material in the 18th century. Over two centuries after their creation, the "character heads" of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt still influence artists with their exaggerated expressions. Their surprisingly modern approach reflects European Enlightenment's emphasis on emotion as well as the contemporary pseudo-sciences based upon facial studies.

|

|

|

|

Click the Display Composite above to visit the Getty Ancient Sculpture page.

|

|

Click the Display Composite above to visit the Getty Bronze Sculpture page.

|

|

Click the Display Composite above to visit the Getty Paintings page.

|

|

Click the Display Composite above to visit the Getty Decorative Arts Index page.

|

|

Click the Display Composite above to visit the Getty Architecture page.

|

|

Click the Display Composite above to visit the Getty Villa section Index page.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|